I WISH I Learned Jazz Improvisation Like This – Stop Wasting Time

- By Jay Metcalf

- Improvisation Lessons

Level up your saxophone playing today!

Check out the audio podcast version of this post on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

For years, teachers told me to “just play what I feel,” which made soloing super frustrating, until I learned that jazz improvisation isn’t some dark mystery. It’s actually an established language we communicate in.

In this article, I’ll explain why that old advice is holding you back and get you speaking the language with some easy-to-play vocabulary that will make your soloing sound legit right away.

I’ve made a PDF download of this lesson for you, which is totally free. Click here to download it.

Improvisation is a Lie

Here’s the dictionary definition of the word improvise:

“To make, invent, or arrange on the spur of the moment without planning. To compose, recite, play, or sing without preparation.”

When I started out, that’s what I understood musical improvisation to be making stuff up on the spot without preparation. And this was a huge trap that held me back for a very long time.

That totally incorrect belief stuck with me until it was finally challenged, and I began to recognize that the great jazz soloists I was listening to weren’t just making stuff up.

Here’s what happened for me.

Just like everyone else, when I began to learn to improvise, a teacher gave me the blues scale and told me to use it to make stuff up. I was told to play what I feel, but what came out of my saxophone made it sound like I felt pretty lame. I know many of you reading can relate to this.

Naturally, I felt as though I must be missing some key information. There must be some other scales I need to know. Or maybe I’m just not playing enough notes fast enough. Many people go on like this for years and never realize where they went wrong.

How I Learned the Truth About Improvisation

It was when I started transcribing solos from my favorite players that I began to notice something very strange. These musicians were repeating themselves a lot. Sometimes playing nearly the same exact thing multiple times in a single solo.

Not only that, I would hear the same exact phrases being played by many different musicians on all different instruments, on recordings that spanned many decades.

Was everybody cheating?

How can this be real improvisation if they aren’t making everything up on the spot every time?

Well, it turns out the word improvisation is a bit misleading.

Jazz musicians are not making stuff up at random and without preparation. They are communicating in an established shared language at a very sophisticated level.

I wish I learned this sooner, because once I figured it out, playing solos made so much more sense and everything I played sounded so much better.

So let’s get you started learning some of that jazz language so we can use it to solo in pretty much any style of popular music.

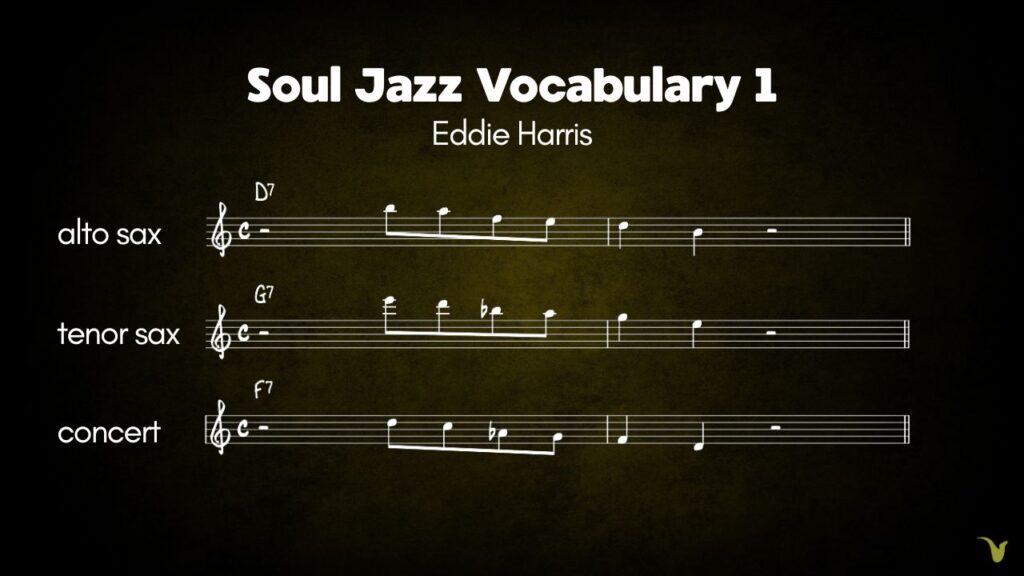

This first line comes from a solo by the great saxophonist Eddie Harris on his tune Cold Duck Time. The key is concert F.

Now, Eddie Harris was not the first person to play this line. And if you listen, you’ll hear something similar to this played on all kinds of recordings since the technology to record stuff has existed.

That’s why we call it vocabulary. It is literally a language that gets passed on orally across generations.

When you use common vocabulary in your solos, listeners understand what you’re communicating because you are speaking a language they have been hearing their entire lives.

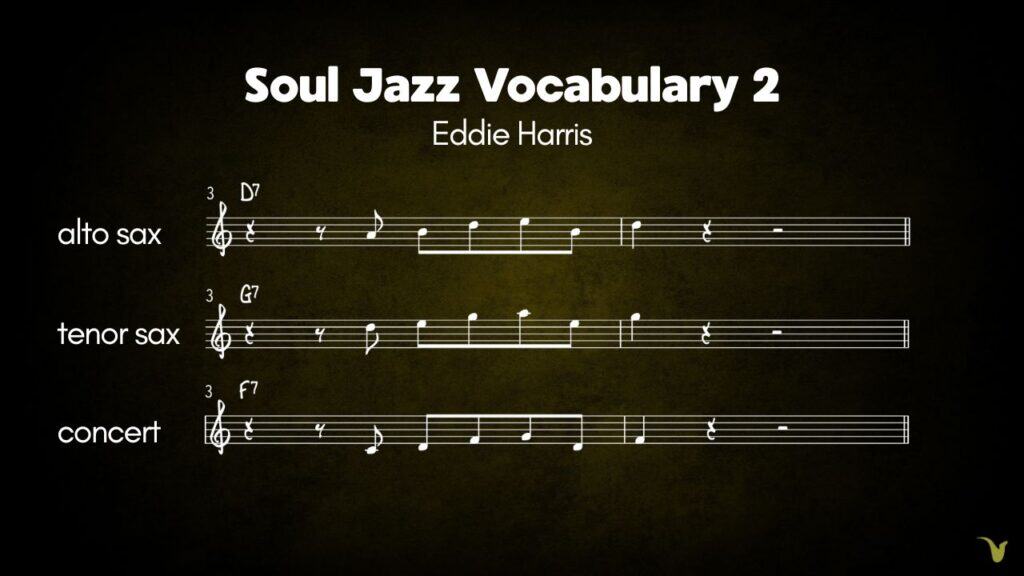

Here’s another one for you.

If you’ve listened to any music of the last century, you have heard something exactly like that many, many times.

So how do we take this musical vocabulary and get it to come out when we play our solos?

You can achieve that by playing a solo using just those two bits of vocabulary. Practice mixing them and experimenting with the rhythm.

If I were learning to speak French, I would learn how to order a coffee, how to ask for directions, how to introduce myself, and many other common phrases. Then I would practice saying those exact phrases every day until they became second nature.

With music, we want to do the same thing. Practice repeating commonly used phrases over and over until they become part of our soloing vocabulary.

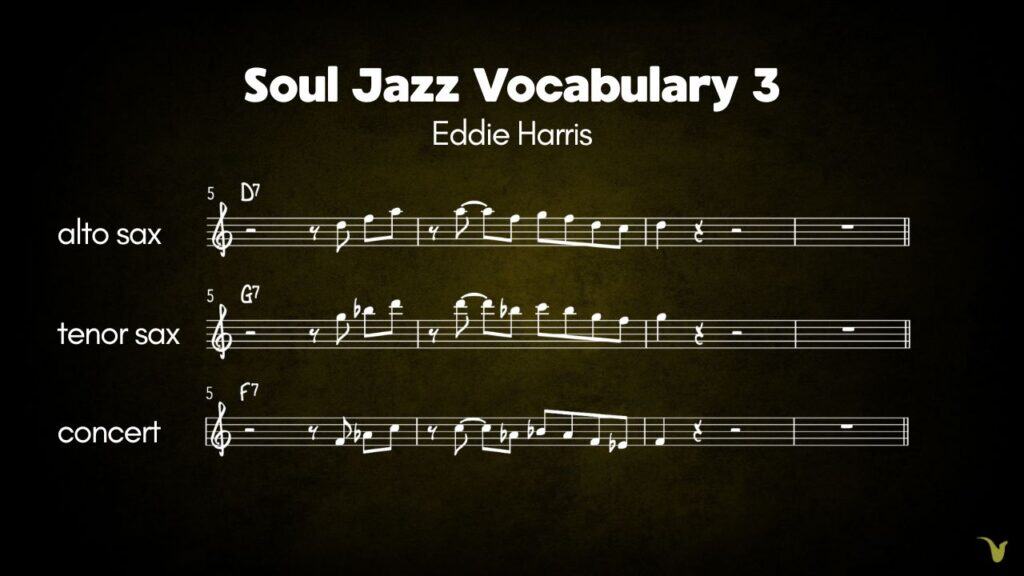

Now here’s one more phrase I lifted from Eddie Harris for you to practice this way.

(Remember, all this stuff is written out for you on the free PDF download.)

Now, you might look at these phrases on the page and say, “Yes, but Mr. Harris is just playing notes from the minor pentatonic scale or the blues scale.” This is true, but it’s the way the notes are combined that makes all the difference.

In the same way that if I were to say the words: appel Jay me je it means nothing. But if I put those same words in a particular order: je m’appelle Jay everyone understands, at least if you took French in high school.

Put on a recording or backing track and practice playing vocabulary over and over again. At first, you won’t have a lot to say. The first month I lived in France, I couldn’t say very much, but I knew how to order a coffee, introduce myself, and ask for directions. Then I got pretty good at saying those things and just kept adding more phrases to my vocabulary over time. That’s what you need to do to become a good soloist.

Figure out the things you want to say and then practice saying them until they come out naturally. Just like with a language, it takes time to achieve fluency, but the process is a lot more fun and rewarding when you do it this way.

By the way, this is the stuff I teach inside the BetterSax Membership every month. And over the years, we’ve had so many players go from totally frustrated to playing their butts off and loving it. If that sounds like a transformation you’d like for yourself, click here to get started.

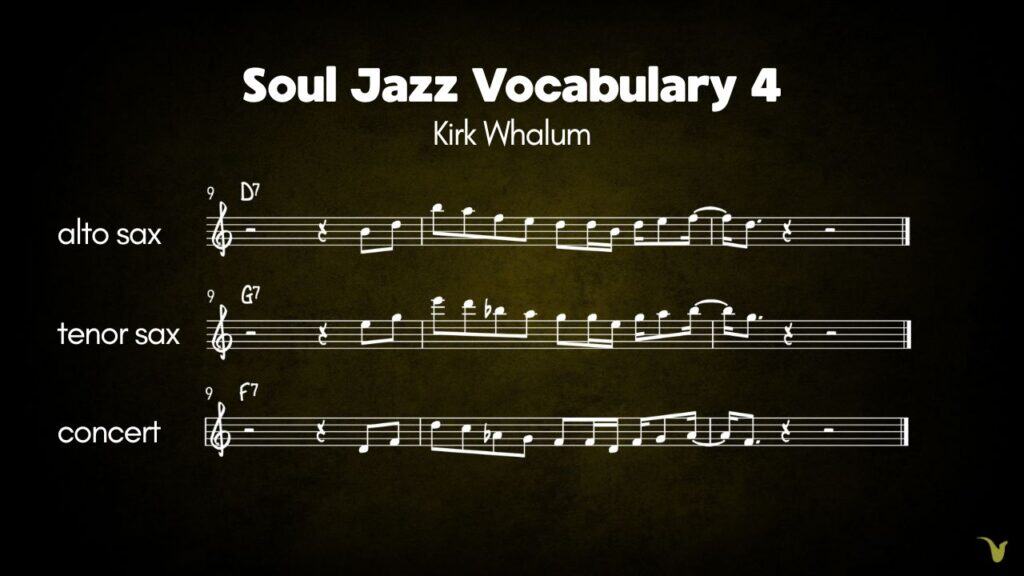

Our next bit of vocabulary was played by the great Kirk Whalum during a live performance of that same Eddie Harris tune, Cold Duck Time.

Now, at this point, you might be asking: “Does this mean I don’t need to learn scales and chords and all that music theory?”

No, it doesn’t. Sorry.

Being able to speak and understand is not enough. We also need to know how to read and write in that language. If you want to communicate beyond the most basic level, you need to learn scales, chords, and music theory too.

But don’t worry, I have an incredibly easy system to help you solo on more complex chord progressions so that you’ll nail the chord changes and stop playing so many wrong notes.

Click here to download the free PDF, and then go read this article next to see how it all fits together.

FREE COURSES

Play Sax By Ear Crash Course

Feeling tied to sheet music? This short mini course will get you playing songs freely, by ear without needing to read the notes.

Beginner/Refresher Course

If you’re just starting out on sax, or coming back after a long break, this course will get you sounding great fast.

More Posts

Jay Metcalf

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *